New Deal Site Preservation

THREATS TO NEW DEAL SITES AND THE IMPORTANCE OF PRESERVATION

Thousands of historically significant New Deal buildings and artworks are at risk today, endangered by neglect, renovations and privatization. The Living New Deal is repeatedly called upon to help with local preservation fights around the country, but we are not equipped to help. We need to step up.

Many New Deal sites are vulnerable and in danger of disappearing. Many are already gone. Although the vast majority are still with us, they are liable to being picked off one by one. If the American people don’t act to save what remains, the New Deal legacy is in jeopardy and the public will forget the amazing accomplishments of the time, along with the memory of what good public policy can achieve and what our grandparents and forebears built in every corner of this nation.

There are many good reasons why certain infrastructure has to be replaced over time. Roads need resurfacing and widening; sewers and water lines corrode; buildings become obsolete; picnic tables decay. Obviously, the constructions of the New Deal era – now almost a century old – have been worn down by time, use and nature, and standards for things like playgrounds and housing have been upgraded. So, we have to expect the inevitable losses of obsolete facilities.

Nevertheless, there are many bad reasons for the loss of historic buildings, once-maintained parks or perfectly useful infrastructure.

One is simple neglect because no one appreciates the significance of a New Deal fountain or post office. Most New Deal sites are not marked and the people who built them or appreciated them in previous decades have passed away; memories fade, along with paint jobs, and the site begins to look tacky and not worthy of restoration.

A second problem, only partly linked to the first, is a pervasive lack of maintenance because local governments are strapped for funds in the post-New Deal age of austerity and tax cuts. The American Society of Civil Engineers reports that the United States has around a $4 trillion backlog of infrastructure maintenance and modernization. We should be grateful that so many public works built under the New Deal were solidly constructed and built to last, like Bonneville Dam, the Bay Bridge and the Lincoln Tunnel.

A third reason, linked to previous one, is that governments looking for income to cover current costs see an opportunity in selling off public assets, like parkland for development or an old city hall for private business use. The worst offender in this regard has been the US Postal Service, which was demoted from a cabinet-level office in 1971 and repeatedly threatened with privatization. In 2007, the USPS was forced by Congress to pay its retirement funds decades in advance (something no other agency does). To raise funds and become more ‘efficient’, the USPS has been selling off post offices at an alarming rate, often along with the New Deal artworks in them.

What we see, then, is a combination of ignorance of the past, neglect of the public sphere by governments, and a blatant disregard for the people’s inheritance for short-term gain, so typical of our age.

None of these things are entirely new nor do they apply only to the New Deal’s legacy of public works. That is why an Historical Preservation movement arose in the early 20th century to protect important parts of our national heritage, beginning with places like Williamsburg, Philadelphia’s Liberty Hall and Civil War battlefields. Indeed, the New Deal put many people to work helping out with such efforts, initiating the Historic American Buildings Survey and doing extensive rehabilitation work on historic sites.

There are thousands of knowledgeable and dedicated people around the country trying to guard the nation’s cultural inheritance. They work in state preservation offices, local historical societies, federal agencies, planning offices, and libraries and archives. Some are specialists in the New Deal or Art Deco eras, but they are few and far between. We need to rally such people to meet the collective challenge of New Deal preservation.

Listings on historical registries (national, state and city) are helpful, but even that is not always enough. Local citizens are a bulwark of preservation but often have nowhere to turn for help. What is needed is a national program to inventory, mark and protect important New Deal public works. The Living New Deal has begun this effort, but it is gigantic and should be taken up by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and federal agencies.

In the meantime, we are here to document the New Deal legacy and to support local communities seeking to stop the loss of treasured New Deal sites. Click on the next tab for a brief with practical advice for New Deal preservationists.

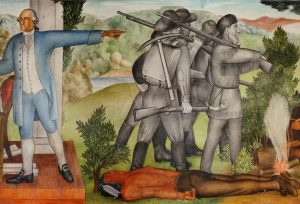

(NOTE: Some New Deal art and monuments offend current sensibilities because of their subject matter, including portrayals of slavery, Indian wars, women and people of color in general. Because those controversies raise a whole other set of concerns about preservation (or removal), we deal those under a separate heading: Endangered New Deal Art).

Trying to preserve a New Deal site, structure, or work of art? Here are some practical tips from The Living New Deal

Below are several strategies for preserving New Deal history from threats of demolition, sale, or other types of loss. We have categorized the strategies, but you should read the whole list to see which ones might apply to the particular situation in your community. The first few suggestions are proactive: these are actions you can take to highlight the importance of local New Deal history before threats arise. As you go down the list, the tips become more applicable to urgent preservation problems.

Make New Deal History Visible

Apply For A Historic Marker or Plaque: Try to get your local government, state government or a non-profit organization to place a historic marker at the site. As examples, see the Florida Historical Marker Program and the Norwalk Historical Society House Plaque Program.

Get It Registered: Try to get the historic site listed on a state or local registry of historic properties. As an example, see the Maryland Inventory of Historic Places.

Obtain National Recognition: If this is a major site or building, consider applying to the National Register of Historic Places or as a National Historic Landmark. Instructions can be found at “Where to Start (How to list a property,” and “Learn How to Nominate a Property for NHL Designation.”

Contact Local Experts and Organizations: In almost every case, it helps to have more and better information about the site, building or work of art, such as who designed it, which agency paid for it, and when it was begun and completed. Your state historic preservation office (SHPO) or local historical society ought to be able to provide useful assistance and advice. The National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers has a directory of SHPOs. Additionally, local history or architectural organizations may be willing to help draft applications for markers and applications to historical registries.

Suggest Practical Alternatives, Compromises, and Incentives When a Site is Threatened With Sale or Destruction

Tax Credits: Check to see if the historic site is eligible for any type of historic preservation tax credit; if so, it can be used as an incentive to preserve or rehabilitate the site instead of destroying it. See, for example, the National Park Service article, “Tax Credit Basics.”

Conservation Easements: Suggest to the owner the possibility of a conservation easement. In these types of arrangements the owner retains possession of the property, but gives development or alteration rights to a preservation trust in exchange for tax benefits. See, for example, the National Park Service article, “Easements to Protect Historic Properties: A Useful Historic Preservation Tool with Potential Tax Benefits.”

Adaptive Reuse: Older buildings can often be modernized on the inside to accommodate present-day uses and technology, while having their exteriors preserved. This may be a point of compromise with those advocating for demolition due to ‘obsolescence’. For more information, see “Best Practices in Adaptive Reuse,” by the Kraemer Design Group, and “How to Support Adaptive Reuse of Historic Buildings,” by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Environmental Benefits of Preservation: According to a 2011 report by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, “Building reuse almost always yields fewer environmental impacts than new construction when comparing buildings of similar size and functionality.” Hence, environmental protection might be a key argument in your overall strategy, and you may want to solicit or demand an Environmental Impact Report (EIR) on the site from your local or state government. Indeed, EIRs are often required for major projects, especially those involving public spaces.

Cost-Benefit Analysis: Consider commissioning a study to determine if preservation would be less expensive than rebuilding or relocating. According to the Work Group for Community Health and Development at the University of Kansas, “Historic preservation conserves resources, reduces waste, and saves money by repairing and reusing existing buildings instead of tearing them down and building new ones.” For example, several historic buildings at the West Virginia School for the Deaf and Blind were saved, in part, because building a new campus at a different location was deemed more expensive (see “School for deaf and blind to stay put,” WV Metro News, October 10, 2013).

Go on the Offensive

Meet with Your Political Representatives: There are likely to be sympathetic members of city councils, county boards, and state legislatures, not to mention staff members of Congressional representatives and local offices of US senators. Do not hesitate to make appeals to these people and insist on meeting with them; they are normally very open to meeting their constituents. Be sure to have your arguments in order before you go, and take along local experts, if possible.

Gather Local Support: If you find that owners or local government are not responsive, devote time and energy to recruiting public support. Many community members and organizations (e.g., museums, historical societies and preservation groups) have a passion for protecting local history. Consider a petition, letter-writing campaign, newspaper ads, community rally, etc. See how a grassroots effort recently saved a historic house: “South Windsor Main Street Residents Save Olcott House From Demolition,” Hartford Courant (CT), May 19, 2016.

Create a Campaign: In some cases, a small group of people, or even just one person, can accomplish a surprising amount. However, depending on your time and resources, and the importance of the site, consider creating (or joining) a wide-ranging campaign to preserve your New Deal history. This might include the creation of a website and working with preservation advocates outside your area. For examples, consider campaigns that have been created to save Post Office history(both structures and art): Save the Berkeley Post Office, The National Post Office Collaborate, and Save the Post Office.

Legal Remedies: Search for state laws or local ordinances (including conservation easements, see above) which might protect the property. See “Local Preservation Laws,” National Trust for Historic Preservation. Consult with local and state preservation organizations for advice. Some law firms will work pro bono or for reduced rates on such public-spirited cases – but beware of running up legal fees!

If New Deal Artwork Is Threatened, Contact the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA): Threatened New Deal artwork may be the property of the federal government. Many such artworks were lost or inappropriately sold off in the past. If the art is indeed government property, it is not legal to sell or destroy the piece, and the GSA can demand its return to public hands. For more information, see, “New Deal Artwork: Ownership and Responsibility,” U.S. General Services Administration.

Buy It: Perhaps your organization or community has the resources to buy the New Deal site or structure in order to save it. See how a non-profit organization and a church worked together to save a historic house from demolition by purchasing it: “Cross-town: Greeley church buys historic home, prevents destruction,” Greeley Tribune (CO), November 29, 2015. Also, see the interesting case of a WPA-built governor’s mansion that has been bought, relocated, and then purchased again through auction: “Old governor’s mansion sells at auction,” Rapid City Journal (SD), August 23, 2013.

By applying one or more of these strategies, you will become a proud defender of the public domain and the historic legacy of your community!

- Vulnerable New Deal Art and Sites

The following is a partial and ever-changing list of New Deal art in need of preservation.

George Washington High School Arnautoff Murals

Luverne, Alabama Post Office Mural

WPA mural at the Memorial Hall at the University of Kentucky in Lexington

Jeanerette, Louisiana Post Office

Father Junipero Serra Sculpture – Ventura CA

Post Office Mural – Madison FL

Post Office Mural – Medford MA

Post Office Mural – Jackson GA

- Postlandia Reports that “USPS Officials Order Historic Murals Covered in 12 States; Considering Removal”

Evan Kalish, Postlandia founder and Living New Deal researcher at large published a post about the recent USPS Officials order to cover historic murals in 12 states. Kalish writes that, “[i]nternal emails obtained via the Freedom of Information Act reveal that an “artwork workgroup” of high-level United States Postal Service (USPS) officials, including attorneys and USPS’s… read more

Evan Kalish, Postlandia founder and Living New Deal researcher at large published a post about the recent USPS Officials order to cover historic murals in 12 states. Kalish writes that, “[i]nternal emails obtained via the Freedom of Information Act reveal that an “artwork workgroup” of high-level United States Postal Service (USPS) officials, including attorneys and USPS’s… read more

THE FIGHT TO SAVE THE ARNAUTOFF MURALS

AT GEORGE WASHINGTON HIGH SCHOOL

In 2019, we joined the campaign to save the historic WPA murals at the George Washington High School in San Francisco after the SF School Board voted to destroy the murals. The Guardian, the New York Times, and The San Francisco Chronicle reported that the destruction of the 1,600-sq-ft New Deal-era murals would cost at least $600,000. Hiding the artwork would cost up to $825,000. An extensive letter-writing, petition and political campaign to protest the loss of this magnificent public art and erasure of the past—albeit a painful depiction of our nation’s history–was ultimately successful and the School Board rescinded its decision after a fierce political fight that ended up costing 3 members their seats on the board. read more